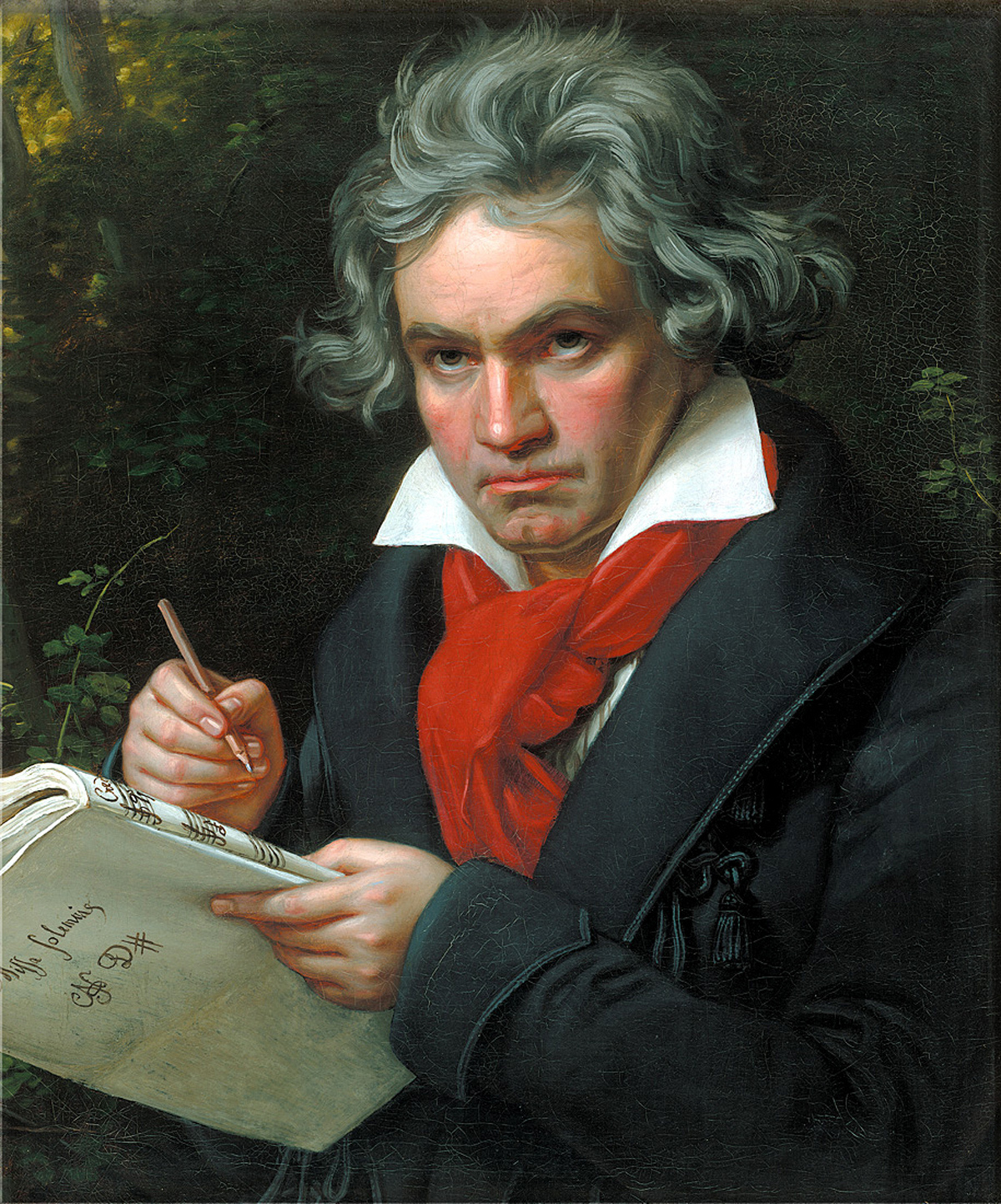

Ludwig van Beethoven

The Classical Period

Joseph Karl Stieler, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Born in Bonn, part of the Holy Roman Empire, Ludwig van Beethoven had grown up with a poor family life. His father was an alcoholic and occasionally abusive, but recognized his son’s talent and pushed him hard, hoping to turn him into a child prodigy like Mozart. A seventeen-year-old Beethoven most likely met Mozart in person during a trip to Vienna in 1787. Reportedly, Mozart agreed to take the young man on as a student, but Beethoven was forced to return to Bonn when his mother suddenly took ill and died. Beethoven returned to Vienna permanently in 1792.

When Joseph Haydn returned to Vienna from his first concert tour in England that same year, he took on the young Beethoven as a student. Haydn reportedly grew frustrated with Beethoven, who did not like keeping to the traditional structures he was taught. Beethoven, in turn, disliked Haydn’s teaching style and frequent trips to London, and sought composition lessons with other prominent musicians in Vienna, including Antonio Salieri.

Beethoven quickly established a reputation as a prodigious pianist, playing “piano duels” and improvisation contests against other performers. He published his first set of piano compositions, Opus 1, in 1795. He began teaching as well, taking on as students a pair of sisters named Josephine and Therese von Brunsvik. Beethoven fell deeply in love with Josephine. They remained lifelong friends, but as she was an aristocrat and he was a commoner, there was little chance of any formal relationship between them.

Although Beethoven would continue to write works for piano, as well as string quartets and religious music, throughout his life, it was his nine symphonies that would make him the most famous composer in the world and a hero to artists for the next hundred years.

His first symphony was premiered in 1800 at a concert along with works by Haydn and Mozart, and established Beethoven as one of the leading composers in Vienna. In his early works, Beethoven wrote in traditional Classical forms, but had already begun to incorporate sudden changes in tonality and an expanded wind section.

Around this time, he began to notice a slight buzzing in his ears. The following year, Beethoven met Giulietta Guicciardi, a cousin of Josephine and Therese von Brunsvik. He dedicated his Piano Sonata No. 14 to her and proposed marriage. Like her cousins, she rejected him due to his social status, his growing fame notwithstanding.

Beethoven soon noticed he was having difficulty hearing high frequencies, and it became clear his hearing was deteriorating. He wrote a letter to his brothers, known as the Heiligenstadt Testament, in which he confessed he was contemplating suicide, but resolved to live on for the sake of his art.

His Third Symphony, premiered in 1804, was dedicated to Napoléon Bonaparte, whom he considered a champion of liberalism and natural rights. When the composer learned that Napoléon had declared himself Emperor of the French, he scratched out the dedication so furiously it left a hole in the front page. That same year, Josephine’s husband died, and Beethoven attempted to reignite a relationship with her. She, however, refused to allow the relationship to move beyond friendship.

Beethoven considered moving out of Vienna, but several wealthy nobleman arranged an annuity to keep him in the city. His Fifth Symphony was composed in 1808 and captures the violent emotional extremes of his life.

Through a friend, Beethoven took on another student named Therese Malfatti. He grew increasingly fond of her and proposed to her in 1810. She rejected this proposal, possibly because of their class differences, possibly because he once got drunk at a party and said something that put her off, and possibly because she was 18 and Beethoven was 40. However, a piece Beethoven wrote around this time was found in her possession after his death. It eventually passed to a German music scholar who misread Beethoven’s sloppy handwriting, causing him to publish it not as Für Therese, but as Für Elise.

Soon, Beethoven had to lay his head against the piano and play as loud as possible in order to hear it. He kept a book in his apartment where friends could write their parts of the conversation for him to read when they visited.

In 1812, Beethoven wrote a famous love letter to someone he referred to as his “Immortal Beloved.” The recipient is unknown. Some have suggested Josephine von Brunsvik, Therese Malfatti, or another friend and potential lover named Antonie Brentano.

By the time of his Eighth Symphony in 1814, Beethoven was completely deaf and retired from public performance. However, he continued composing in his head, writing his monumental Ninth Symphony and his mass Missa Solemnis in 1824. He did conduct the Ninth at its premiere, and after the finale, forgot his deafness, thinking the silence meant the audience did not appreciate his work. The concertmaster had to turn him around to see the audience's enthusiastic cheering.

Beethoven grew terminally ill in 1827 due to liver and kidney failure. He received the last rites on March 24, after which he is said to have remarked, "Plaudite, amici, comoedia finita est” (“Rejoice, friends, the comedy is ended.”) He was then informed that a friend had sent him twelve bottles of wine. His last words were, “Too bad, too late,” after which he fell into a coma. Two days later, there was a violent thunderstorm. Beethoven is said to have shaken his fist at the sky and then died.

His funeral in Vienna was attended by nearly 30,000 people. He instantly became an icon of the artist struggling against fate, and not only his compositions but his life itself paved the way for the Romantic Period.